Is Node.js Better?

NOTE: This is essentially a transcript of (though mostly written before) my JSConf 2012 talk, "Is Node.js better?". It's long, I know. There is no tl;dr, sorry.

Is this better than that?

This is a question that we confront constantly. Numerous times a day, in fact. And sometimes a lot rides on the answer. Is this job offer better than that one? Is this car better than that one? Is this home for my ailing mother better than that one? Is this billing system better than that one? Is this tax plan better than that one?

This question is everywhere. We cannot escape it. Yet for the frequency with which we confront it, our approach to resolving the question is quite likely not objective. Which is to say, we are probably not answering the question in a way that is mostly likely to benefit us. Many used car sales, software system sales, and political campaigns, to mention a few things, profit from our incompetence answering this question. We'll consider some of the reasons why that is true later. But just recognizing this is rather distressing.

But we're not just asking, "is this better than that?" in general; we're here at JSConf and this talk is about Node.js. Why? You probably know that I'm not a notable member of the Javascript community. I have not authored a single JS library. I've never given a talk at a JSConf. Why am I here? And why am I talking about Node.js?

I met Chris Williams at CodeConf 2011, organized by Github. Chris sat down next to me during the Node.js talk by Ryan Dahl. I found the talk fascinating because much of it focused on improving the non-blocking I/O facilities in V8 for both Windows and Unix-ish platforms. This was something that we have a lot of interest in for the Rubinius project and I had then recently started porting Rubinius to Windows.

At the time, I had no idea who Chris was. But we chatted a bit and at the break, Chris stood up and said, "I'm going to get some more beer, would you like some?" Holy shit. That's why I had been smelling beer for the last 45 minutes! Chris had a coffee cup full of beer. Hilarious. One person's moderation is another person's excess.

I declined the beer then but we exchanged contact info and Chris put me in touch with folks from Microsoft who were assisting with getting Node.js running well on Windows. Chris also informed me of the upcoming JSConf that was being held in Portland, where I live. It was too late to get tickets but I was able to attend the opening party and made a point to hang out as much as I could with the other attendees at conference events. At the time of CodeConf, I was merely curious about Node.js, but I didn't have much of an opinion.

Fast-forward almost nine months. I was seeing a flurry of tweets about Node.js. This got my attention, in part because of the people who where tweeting about it. I use Twitter as one of my main sources of information about developing technology. The more tweets I saw, the more uneasy I felt. Finally, one morning I posted this:

My intent was not to be antagonistic. Rather, my challenge was focused on finding out what sort of problems people were solving with Node.js. But any challenge, even a sincere one, carries a connotation of aggressiveness. And it is a fact of human nature that when pushed, people tend to push back. Some of the responses to my tweet attempted to share knowledge but others were understandably of the genre, "if you're looking for a fight, you'll find one here."

It wasn't long before Chris DM'd me and basically said, "What's up with this 'challenge'? You are working on important stuff, why are you wasting time on this?" I answered that I was genuinely interested in understanding why people are using Node.js. We exchanged a few comments over a several days and Chris asked if I was willing to do a talk on the subject. So that is how I got here, talking about Node.js at JSConf. It is a honor and privilege to be here and I thank Chris and the conference organizers, as well as all of you.

So who am I? I've been working on the Rubinius project for the past five years, and four of those while employed full-time by Engine Yard. I started the RubySpec project as part of my work on Rubinius. Through my work on Rubinius, I have learned a lot about compilers, virtual machines, garbage collectors, and importantly, concurrency. One of the notable points about Rubinius is we have removed the global interpreter lock (GIL) so that multiple native threads can run Ruby code in parallel on multi-core or multi-CPU hardware. We see this ability as vital to the success of Rubinius.

Now that you know how I came to be speaking at JSConf and you know a little about what I do, the question remains, "Why am I speaking at JSConf? Why do I care about Node.js?" The answer to that will take us on a journey through some interesting territory. I only ask that you suspend prejudice and follow along. If you ultimately disagree with me, there is nothing wrong with that.

Organizations tend to perpetuate the problem they were created to solve.

I don't remember exactly when I was introduced to this idea, but it had a significant effect on me. There are a lot of difficult problems to solve in the world and one of the first things we tend to do is create an organization that is dedicated to some aspect or another of a solution. Notice that there is a difference between people organizing to solve a problem and an organization. As soon as we have an organization, it will tend to take actions to perpetuate itself. Of course, these actions are really the decisions of people in the organization. The organization has no effective power independent of the people who comprise it, yet the organization as a whole is a system, and will tend to exhibit life-preserving actions. If an organization exists to solve a problem, and that problem is solved, the organization ceases to have a reason to exist.

Every time we organize for any reason, there is a tendency for structures to solidify. The rigidity of those structures tend to inhibit movement and change as circumstances change. Therefore, a vital force in social organization is the force that opposes established order. There is a name for this force: subversive, something seeking or intending to subvert an established system or institution. People who participate in subversive activities are called subversives.

There is another aspect to this that is important. People tend to be in one of two groups: those who fear change and those who create change. When we think of "change", it usually has a positive connotation, and "subversive" has a negative connotation. But they are often the same thing. Change can be positive or negative. But as it has been said, "there is only one constant: change."

Javascript has been an amazing technology wielded by people who have radically and fundamentally changed how we interact on the web. This is fascinating and tremendously valuable for societies all over the world. So part of the reason why I'm speaking here is that people enthusiastic about Javascript are people who are creating change. I want to acknowledge, assist, encourage, collaborate with, and influence people who are actively working to change the world for the better.

This talk is about conflict resolution. Conflict is inherent in the question, "Is this better than that?"

It's important to note that any contrast implies conflict. Sometimes people assert that you should be able to promote something without saying anything bad about something else. This idea is impossible to comprehend. If I say, "water is good," it is inherent, even when implicit, that I'm saying water has value and value is a concept that relies on a context and a standard. There is no concept of value that is not relational. Something is only good relative to what you are judging it against.

Criticism is advocacy; advocacy is criticism. Criticism is also controversy and controversy is entertaining. However, despite the entertainment value, different ways of resolving conflict can have very negative consequences. Usually when there is conflict, we address it with aggression. We talk about having a "shootout", "fight", "throw down", etc. But are fights a healthy, beneficial way to resolve controversy?

Further, when a person comes out as a strong advocate for some technology, people opposed to the technology will hurl the epithet "fanboi" as an attempt to discredit the idea by attacking the person. From the other direction, if we don't like someone's criticism, we may call the person a "troll".

Other times, we will simply attempt to avoid conflict entirely. In Ruby, there is this idea, MINASWAN: Matz is nice and so we are nice. There is nothing wrong with being nice, but why is "nice" contrasted with "criticism"? Are we supposed to never challenge someone because being "nice" is more important and challenging them is inherently not nice? What if someone is doing something that from our experience is not beneficial to themselves or others?

For the most part, this is how I see us dealing with conflict. We either avoid it or we attempt to devalue the person rather than discuss the idea. This is dysfunctional. Basically, we suck at conflict.

How can we improve how we deal with conflict?

I assert that we need to use science. But how? What does that mean? To understand this, we need to look more deeply at how we as humans think. But before we get to that, let's consider a very common aspect of social organization: the tendency to surrender our own judgment to that of an "expert".

In 1948, Alex Osborn, who was an ad man at B.B.D.O., wrote a book, Your Creative Power, where he introduced "brainstorming". Essentially, a group of people toss out solutions to a problem under consideration. The emphasis is on generating as many ideas as possible. A key element of the activity is that everyone is told not to criticize their own or other's ideas. It was asserted that creativity was too delicate a process to withstand the harsh light of a critical challenge.

Of course, that made a lot of sense to people. Over the years, brainstorming has been used extensively in problem solving. It is still heavily used. The problem is, the method is flawed. The proscription against criticism happens to be wrong.

There were two studies that tested the two main components of the brainstorming methodology for discovering creative solutions. The first focused on individuals versus groups. The result was that people working alone produced not just more but better ideas than the groups.

The second study focused on the suspension of criticism. The subjects were divided into three groups. The first group were instructed to use brainstorming and told not to criticize their own or each other's ideas. The second group were instructed to challenge and debate one another. The last group was allowed to organize themselves without any instruction in a particular method. The results from this experiment were unambiguous. The debaters significantly outscored both other groups. The act of criticizing other's ideas causes both the questioner to understand the idea more fully and the person proposing the idea to go more deeply into it.

The important lesson is two-fold. Criticism is an important aspect of creative, intellectual effort. Despite the proscription against criticism having superficial validity, it was rather easily disproved.

Another interesting study related to creativity examined whether there was a correlation between the success of Broadway musicals and how well the team producing the musical knew each other. The measure of team familiarity was named the Q factor. A team where all the members had worked together before would have a high Q factor. A team where no members had worked together before would have a low Q factor. The study found that there was indeed a significant statistical correlation between Q factor and success of a musical. In other words, a certain range of Q factor was a good predictor of success. The value of Q that was most likely to predict success was from a team where most members had worked together previously but some members had not. A team where no one had worked together wasn't able to communicate effectively enough. A team where everyone had worked together didn't benefit from an outsider's perspective challenging ideas.

These results are reported in Groupthink: The Brainstorming Myth by Jonah Lehrer, published in New Yorker magazine, January 30th, 2012. The lesson we can take is that criticism is important to creative solutions to problems and we should be seeking people who are unfamiliar with our favorite language or framework to join us and help our understanding of problems and the solutions we are building.

Another lesson is that there is nothing that prevents a well-meaning and experienced expert from being wrong. One thing that we should all be challenging is "appeals to authority" in decision making. As you can see from the following tweet, Ward Cunningham thinks Node.js is the future of the server side. However, that assertion is most likely not taken by readers of the tweet as a neutral assertion of fact about Ward's opinion. It is taken as meaningful because Ward said it. Further, it is unremarkable that the assertion is unaccompanied by any evidence with which to help determine the validity of the assertion. Assertions by experts with no accompanying evidence are the status quo in our industry, and that should be extremely embarrassing.

The next part of our journey takes us to one of the most interesting books I have read. Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011) is a book about how our minds work. There are basically two modes that have distinct and surprising features in the way we think. These two modes influence one another.

One mode is called fast thinking because our brains activate an entire network of associations in a sub-second burst of activity. For example, if I display the word "bacon", you will immediately have numerous memories and associations with bacon coming into awareness. This fast mode is all about pattern matching and the associations activated can be extensive and surprising. In this mode, the brain over-achieves, if you will. It activates far more associations than may be needed. And some associations may be surprising. It is up to the second mode to use those associations depending on the task we are confronted with.

The other mode is called slow thinking and is related to such activities as concentration, judgment, monitoring, and selecting. If I ask, "what is 23 x 47?" Answering this requires deliberate application of a set of tasks to arrive at the answer, unless the problem is one we are quite familiar with, in which case the fast thinking would just produce the answer as an association.

The book is filled with fascinating knowledge about how our thinking works and I cannot recommend it highly enough. It discusses numerous ways in which our thinking can produce erroneous beliefs and ideas. One of the very interesting results is that our deliberate, slow thinking can be easily fooled into accepting a wrong answer provided by our fast thinking mode if we feel at ease. But if we feel anxious, our slow thinking mode will be more critical and less likely to just accept an answer provided by our fast thinking mode.

Reading Thinking Fast and Slow and reflecting on the complex and inter-related behaviors that scientists have been able to discover facts about led me to the following conclusion:

Programming is a behavioral science.

Behavioral science is a very broad category that encompasses disciplines that explore the activities and interactions among organisms through systematic analysis and investigation using controlled observation and scientific experimentation.

There is a distinction between programming and computer science. Writing software is an activity that is mostly centered on human behaviors. Most software will interact with people at some point. Basically, it is written by people, for people, and funded by people. Of course, there are mathematical foundations of computing and algorithms, but those are rarely the most important elements of the process of creating software.

If you are familiar with the many methodologies under the "Agile" umbrella, you know that dealing with changing requirements is one of the most complex aspects of software construction. But note that those changes are almost entirely due to human behaviors. If we build a bridge, an environmental study will determine most of the forces that the bridge design must account for. Further, the laws of physics are quite well established. Engineering the bridge is not a terribly complex activity. However, in software, there is not a good way to clearly establish the constraints for the system we are building. People are responsible for most of the complexity in programming. That is why I assert it is a behavioral science.

What is curious to me is that a typical undergrad psychology student will likely have more exposure to research methods than a typical computer science undergrad or even graduate student. Research methods are activities directed at determining the validity of assertions. They are what enable us to separate knowledge from opinion. Fundamentally, they are related to two aspects of existence: the nature of the world (meta-physics) and the theory of knowledge (epistemology). To learn more about this, I would recommend Research Methods: the basics by Nicholas Walliman (Routledge 2011).

Turning from this general information about applying science to thinking and learning about research methods, let's look at Node.js again. One of the major assertions about Node.js is that it permits writing efficient web servers that must deal with many concurrent connections. So, let's look at some basic features of concurrency, including a possible definition of concurrency.

People are selfish, lazy, and easily bored.

I say that without any moral judgment. I think these are all biologically desirable features of organisms. We are selfish because we are responsible for our own well-being. We are lazy so we don't waste precious and costly-to-obtain energy. We are easily bored because we must constantly incorporate new material to maintain our existence. Of course, each of these attributes has an opposite and any individual will exhibit a combination of these behaviors. But these three attributes are interesting to consider in this context.

Scarcity is a fact of life. Infinity is a mathematical fantasy. There are a finite number of computers.

Combine scarcity with the attributes above about people and we have a reason for concurrency in computation.

When a single CPU with a single core is running, it can basically execute one instruction at a time. Of course, this is a simplification, but it is basically true. If we consider a program to be a sequence of instructions, I1..In, every possible ordering of those instructions is a plausible definition of concurrency. For example, a four instruction program could be I1, I2, I3, I4 or I3, I1, I2, I4, etc. Not all orderings are going to be meaningful given the semantics we expect from the program.

Now, consider that the program would be 100% efficient if all the instructions are dedicated to solving the problem for which the program exists. However, if any instructions are dedicated to changing the order of instructions, those would reduce the efficiency of the program by doing work that is not directly related to solving the problem.

Once upon a time, computers solved problems one at a time. The jobs were processed from start to finish one at a time. This is great for efficiency but not great for people. People don't want to wait for everyone else's job to finish before theirs. Nor are they willing to do a lot of extra work to make the computer most efficient. So the idea of time-sharing systems was born. Essentially, everyone got a little slice of time to use the CPU. Even though some efficiency was lost, and so everyone's program would ultimately take longer to complete, the average time to wait went from hours (a whole day, perhaps) to possibly a few minutes. Computers became interactive.

There are only a few mechanisms to re-order the instructions of a sequential program. (Note that we can generalize from the instructions of a single program to the instructions of a set of programs concatenated together. The fundamental considerations do not change.) One way would be to do a little work and then voluntarily yield control of the CPU to another program. At some later time, another program would yield control back to us. This would implement cooperative multitasking. Another way would be for some sort of supervisor to allocate a short amount of time to each program in sequence. This would implement pre-emptive multitasking. Once your time-slice is over, you simply have to wait until everyone else gets a time-slice before you can run again. Yet another way would be to allow a program to run until it performed some action, like writing to the display or reading from the disk.

Each of these mechanisms for interleaving the instructions of a serial program may have different trade-offs, and consequently, different efficiencies. However, there is nothing inherent in any method that dictates it would be more efficient than any other. I consider this a very important point missing from almost every assertion about the uniqueness of Node.js. People are saying, and others are repeating, that Node.js enables solutions that are not possible with other programming languages and frameworks. This is absolutely false.

There is a lot more to understand about concurrency, modern CPUs, and efficiency than we can cover here. However, if you are concerned with the validity of the assertion that Node.js is good technology for writing efficient web servers, then you may want to understand more about concurrency.

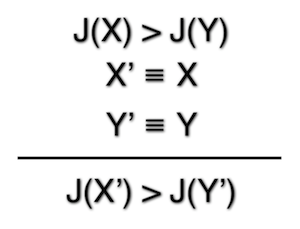

Besides concurrency, there are a number of justifications given for using Node.js. Are these justifications valid? I think consistency is important. If I say X is better than some Y because of some reason J, and there is some X' that is basically equivalent to X and Y' equivalent to Y, then X' should probably be better than Y' for the same reason J. That idea is expressed in symbols below, where the long horizontal line means that the statements above logically imply the statement below the line.

One reason given for using Node.js is that the same language, Javascript, can be used on both the client and the server. If that is true, then why shouldn't someone use GWT and use Java on both the client and server? Since the JVM works very well on the server, certainly the effort put into GWT could be seen as the equivalent of the effort put into Node.js to make a browser technology work well on the server. At the least, when you hear the "same language" justification, you should be looking for places where the same justification could be made but you don't find it convincing. If the justification isn't convincing when you substitute analogous elements, then either the justification is flawed or it is missing something that would differentiate the two situations.

Often, the same language justification for using Node.js is promoted by people who are also bragging about being polyglot programmers. Not only is knowing more than one programming language beneficial, it's basically required these days. But if knowing more than one language is offered as a positive, why is it important to use the same language on client and server? I'm not saying this argument is invalid, but rather that the justification should examined for consistency.

Another reason given for using Node.js is that there are many Javascript programmers. However, statistically, that means there are many mediocre or poor quality Javascript programmers. And if concurrent applications are so hard, do you want a lot of mediocre or poor programmers building them? Again, many Javascript programmers may be a justification for using Node.js but by itself, the justification is problematic. It's likely an extreme over-simplification. As such, it has dubious value as more than just a convenient dismissal of someone who challenges the rationale for using Node.js.

It may be that using Node.js is just more fun for many people. This is a great reason to use Node.js. However, it is not one that can be used to evaluate the technical merit of the technology. Which is fine. Recall that I'm asserting programming is a behavioral science. We should be studying and giving adequate weight to considerations that are not merely technical. Humans are using Node.js.

Finally, despite being controversial, I'm going to give some opinions about Node.js based on my experience. The point is not whether you believe me or not. These opinions should be examined critically with the objective of determining their validity using methods suggested above.

More CPU cores is the trend for the future. Typical programs have a huge amount of state. Every library loaded is program state. Running multiple processes demands duplicating the memory used by each process times the number of running processes. As long as the total memory needed to saturate the CPU cores is less than the memory available, using processes should not be a problem. However, we have seen in Ruby, at least, that it is not typically the case. Memory pressure is a constant problem. Solutions to this memory pressure like copy-on-write (CoW) friendly garbage collection are hard and not guaranteed to be that effective. If the mutable part of the heap is small then there is also very likely little shared state that would complicate simply using threads. If the mutable part is large, you get the same memory pressure over time regardless of CoW-friendly GC.

Since it is extremely unlikely that Javascript will add threads to the standard, Node.js will either be essentially single-threaded or programs will use non-standard libraries to introduce threading. This forces Node.js to use process concurrency to achieve parallelism. In this respect, I think that Node.js rejects the multi-core reality that confronts us.

In fact, Node.js is already confronting the issue of process concurrency. In Ruby, we have Passenger for managing multiple worker processes. There is now a similar system for Node.js called Cluster.

Another concern is that an entire ecosystem of libraries and tools must be built up for Node.js. Javascript was confined to the browser of a long time, and that environment is quite impoverished. In building those libraries, many mistakes that have been make in other languages will be made again. That is simply the nature of humans doing work. We make mistakes. Ruby and other languages have repeated mistakes from languages that came before them. I'm not saying that the work that must be done won't be offset by its future value. I am saying the work must be done and its value should be questioned. There is always an opportunity cost for choosing to do an activity. It is the cost of not doing another activity. In attempting to answer the question whether Node.js is better for our problem, we must consider these issues.

Concurrency is definitely a concern for practically every currently popular programming language. If you have heard that Node.js enables solutions not possible in other languages, I encourage you to look more deeply into the situation. In Ruby, I recommend checking out the Celluloid project by Tony Arcieri. The project's aim is to bring various concurrency mechanisms to Ruby. He is someone with a lot of experience and accomplishments and I'm confident his projects will advance the state of the art in Ruby and hopefully other languages as well. If you are a Clojure enthusiast, you may want to look at Carl Lerche's momentum project. Of course, there are many languages and frameworks that handle concurrency and more are under active development. Node.js is not new technology; it's merely new for Javascript.

Ultimately, the answer to, "Is Node.js better?" is not that important. People will use Node.js even if it's not the best solution to their problem. Other people will not use it even if it is great for their particular problem. Both results limit the benefits available to all of us. Further, we will continue to confront the question, "is this better than that?" If we improve our ability to answer that question, hopefully we will increase the benefit to us all.